END PRODUCT

INTRODUCTION

The two-century slumber: Overview of the Japanese economy during the Edo Period

From the years 1639 to 1853, the people of the Japanese islands were nominally cut off from other nations under the policy of Sakoku (鎖国) which means ‘closed country’. Sakoku was put into effect and gradually tightened over a series of edicts proclaimed by the first three Shoguns, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Tokugawa Hidetada, and Tokugawa Iemitsu of the Tokugawa Shogunate which ruled the country from 1603.

External Trade during Sakoku

During Sakoku, Japan maintained limited trade with certain countries such as China, Joseon (Korea) and even the Dutch.

This trade was restricted to a small island called Dejima in Nagasaki.

Dutch Trade with Japan

The Dutch traded with Japan through the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or the Dutch East India Company on Dejima.

For Japan’s case, the desire for imports, especially silk to satisfy the high demand from Daimyo and Samurai alike is what fuelled the drive for promoting trade. CULLEN, L. (2017)

For the Dutch, their aim was to get their hands on Japanese silver. Keep in mind that during this period, silver was important in the money supply of many nations, and the output of silver in Japan was massive by global standards

Production of Precious Metals during the 16th to 17th Centuries

Japan produced 200 metric tons of silver per year during this period, making it the world’s second largest producer, just behind Spanish America’s 300 metric tons per year. Flynn D. O. (1991)

Gold has also been produced in large quantities for hundreds of years in Japan. By the mid-16th to 17th century, prominent Daimyo like Takeda Shingen of Kai Province began developing gold and silver mines within their domains in order to increase their output and finance the maintenance and expansion of their armies and territory.

In the case of Shingen, after developing a gold mine in his domain, he used the gold produced there to mint and circulate his own currency of Koshu Kin or Koshu Gold. (The Production and Use of Gold in Japan, 2022)

Production of Precious Metals during the Edo Period (17th – 19th Century)

After the last of the three great unifiers Tokugawa Ieyasu had established his Shogunate/bakufu and capital in Edo and laid the foundations for over 200 years of peace. The Shogunate continued to pursue the development of mining for precious metals. (The Production and Use of Gold in Japan, 2022)

Two gold mines, the Sado Kinzan gold mine (1601 – 1989) located on Sado Island and the Toi Kinzan gold mine (1601 – 1965) located in present-day Shizuoka prefecture were the first and second most productive gold mines in Japan respectively for the entire duration of the Edo Period. Other notable mines operating during this period include the Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine and Besshi Copper Mine.

Sado Kinzan produced 78 tons of gold and 2,300 tons of silver for the entire 388 years of its operation from 1601 to 1989. Experience (2012)

Toi Kinzan produced around 40 tons of gold and 400 tons of silver for the 364 years of its operation from 1601 to 1965. (Toi Kinzan Gold Mine, 2024)

Currently both mines are open for tourism and remain popular destinations for tourists today. Interestingly, Toi Kinzan boasts the largest gold bar in the world as an attraction, the bar itself weighs 250 kilograms.

Monetary System of the Tokugawa Bakufu during the Edo Period

Rice Economy

The foundation of Japanese government, society and economy laid upon rice. The position of a Daimyo and their vassals in the hierarchy of the Tokugawa Shogunate was determined by the estimated total volume of rice produced from the arable land in their domain. (Rice and the Economy | About Sumitomo | Sumitomo Group Public Affairs Committee, n.d.)

This volume of rice was measured in Koku (斛) which is equivalent to 180 liters or 150 kilograms of rice. A single of Koku was supposedly enough to feed a single person for one year. Farmers living in the domain of a Daimyo were also taxed based on the amount of Koku, and paid taxes in the form of rice to their Daimyo.

Commodity Currency

In 1601, Tokugawa Ieyasu began issuing gold and silver coins minted in uniform shapes and standards known as Keicho coins. Copper coins known as Kan’ei Tsuho were introduced in 1836 to ensure a stable supply of copper coinage in the money supply.

Later, the Tokugawa Shogunate started to issue gold, silver and copper coins as a form of currency with independent value. The gold coins (Koban, Ichibu-kin) were issued as currencies by denomination, and the silver coins (Cho-gin, Mameita-gin) were issued as currencies by weight. The copper coins were denominated as one mon each. (Historical Events and Currencies in Use: Contents - Currency Museum Bank of Japan, n.d.)

Paper Currency

The late Azuchi-Momoyama period around 1600, also saw the first use of a paper currency in Japan. The first notes were privately issued, known as Yamada Hagaki in the Ise Yamada area (modern-day Mie Prefecture), and were used as a medium of token change in Isenokuni-Yamada (Ise Province-Yamada) amid a shortage of small change in this region. Seno’o (1996)

Yamada Hagaki & Kinai Koshihei

These notes were backed by a certain amount of silver and were used concurrently with coins in the Kinki region of Japan containing Kyoto and Osaka. This region had been economically developed by commercial trade and Shinto religious pilgrimages for centuries since the Heian Period.

These notes circulated in the area of Ise Shinryo, for a period of 300 years.

Over time, a myriad of different paper currencies inspired by the Yamada Hagaki started to be issued and used in neighbouring areas of the Eastern Kinki region like Uji, Matsuzaka and Isawa.

For example, ninsoku tegata, which were payroll-notes also backed by silver issued in Osaka in 1617 to pay for Edo Moat’s construction, the fudazukai, which were paper currencies used as a means of payment between merchants and other silver backed notes issued by merchants in Settsunokuni Hiranogo and Yamato Shimoichi.

Collectively, these privately issued notes are called Kinai Koshiheu, meaning “old paper currency of the Kinki region”, and they would continue to circulate until the Tokugawa Shogunate’s monopoly on currency issuance was established. Seno’o (1996)

Hansatsu

The Hansatsu (藩札) were a form of paper currency. ‘Han’ refers to the domains governed by a Daimyo, and Satsu meaning a banknote. These currencies were issued by each individual daimyo within their domains, out of the roughly 275 Han, 200 of them issued their own Hansatsu.

They were first issued in 1661 by the Fukui Clan and circulated in their domain of Echizen Fukui. RAMOS (2015)

The Hansatsu were also issued by cities and temples in Japan, and were expressed in values of silver, gold, copper and sometimes in rice equivalent, or even wine and oil.

Since the beginning of the Edo Period, the Tokugawa Shogunate had attempted to monopolise the issuance of currency by unifying the entire currency system. Thus, when Hansatsu began to be issued by more and more Domains, the Shogunate maintained a wary stance in regard to them, after all they could potentially fund threats to the Shogun’s grip on power through its monopoly on the money supply.

Unfortunately owing to the rising demand for currency with the growth of the Edo Period Japanese economy from the Kan’ei era (1624 – 1644) to the Genroku Era (1688 – 1704), severe currency shortages in the big cities of Edo, Osaka and Kyoto as well as rural areas and the countryside forced the Shogunate to relax its own currency policy and permit Daimyo to issue Hansatsu for means of local payments and to finance their budget deficits. Seno’o (1996)

Black Ships & the Kanagawa Treaty

On July 8 1853, a fleet of black ships arrived off the coast of Japan and anchored at the entrance of modern day Tokyo Bay at Uraga. Shortly after anchoring, the ships drew large crowds of observers and sightseers who clamoured to catch a glimpse of the ships. An observer who worked in shipping described the sight as akin to looking at castles floating in the ocean, noting the paddle wheels and cannons onboard the large vessels. Takeomi (2023)

This fleet of ships sailed under a flag of stars and stripes, it was a US Navy Fleet and the man leading this fleet was Commodore Matthew Perry.

Commodore Perry arrived bearing gifts for the Emperor of Japan, including a working model of a steam locomotive, a telescope, a telegraph, and an assortment of wines and liquors from the west. He also had with him a letter from US President Millard Fillmore addressed to the Emperor. (Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations - Office of the Historian, n.d.)

A few days after arriving, the ships would leave and sail to Naha in the Ryukyu Kingdom – modern-day Okinawa Prefecture (then a vassal of the Shimazu Clan), but they would be back.

In February 18 1854, the black ships returned and anchored near the Yokohama and Koshiba (at the time both villages) and Negotiations between the US and Tokugawa Shogunate began in Yokohama on March 8. On March 31, the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (神奈川条約), or the Convention of Kanagawa was signed. Takeomi (2023)

The Articles of this treaty included among others:

-

Two ports (‘Simoda’ – Shimoda and Hakodate) granted by the Japanese Government as ports for the reception of American ships, where they can be supplied with wood, water, provisions, coal and other articles.

-

Whenever ships of the United States are thrown or wrecked on the coast of Japan, Japanese vessels will assist them and carry their crews to either of the two treaty ports Shimoda or Hakodate where they will be handed over to their countrymen.

-

Citizens of the United States temporarily living in Shinoda and Hakodate will not be subject to any restrictions or confinement such as the Dutch or Chinese in Nagasaki, but shall be free to go wherever they please within seven Japanese miles (ri) from a small island in Shimoda harbour.

-

All future privileges or advantages (concessions) granted by Japan to other foreign powers in other treaties would also be granted to the United States and its citizens (Most-favoured nation clause).

-

The United States has the right to appoint consuls or agents to reside in Shimoda at any time after eighteen months from the date of signing of the treaty.

(Treaty of Peace and Amity Between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan (Convention of Kanagawa) - “the World and Japan” Database, n.d.)

The Shogunate's signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa would have an unforeseeable impact on Japanese civilisation as the coming period of contact and trade with the west the treaty heralded would spell the end of the shogunate's grip on power, the samurai class and the rise of the Empire of Japan.

CHAPTER ONE

The Bakumatsu Period and Meiji Restoration

At the tail end of the Edo period, the political situation in Japan was deteriorating rapidly. This period would come to be known as the Bakumatsu Period. The Sakoku edicts implemented by the first three Tokugawa Shoguns limited contact with the world outside Japan and prevailed for over two centuries, during this period, the country experienced generations of peace, a massive population boom, and steadily rising standards of living. All of this was blown up by the arrival of Commodore Perry’s black ships in 1853 and the signing of the Kanagawa Treaty in 1854.

The Other Unequal Treaties

A few months after the Americans concluded their first-but not last treaty with the Tokugawa Shogunate, the British signed the Convention between Great Britain and Japan (Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty) in October 14th 1854.

The terms of this treaty included opening the ports of Hizen – Nagasaki, and Matsmai – Hakodate to British ships for repairs, and obtaining provisions and supplies like fresh water, allowing ships in distress to enter other ports in Japan and also included a most favoured nation clause. (Akihiko, n.d.)

A year later the Russian Empire secured their treaty with the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia (Treaty of Shimoda) in February 7th 1855.

Terms of this treaty included the establishment of the boundary of Japan and the Empire of Russia to be between the islands of Yeterofu – Iturup (Japanese) and Urutsufu – Urup (Russian), opening of three ports Hakodate, Shimoda and Nagasaki to Russian ships to make repairs and procure supplies like wood, water and coal, establishing forms of payment for these services to be in the form of gold, silver, copper cash or in goods and merchandise. Furthermore, this treaty also introduced a clause of extraterritoriality for Russian subjects living in Japan, whom would not be subject to laws in Japan but rather the laws of their own country (Russia). Finally, like the previous two treaties, this one also secured a most favoured nation clause for Russia. Corcuera (2016)

After this period, several other European empires secured further treaties with Japan in 1858 including the Netherlands (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the Kingdom of the Netherlands), and France (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan), while the US, Russia and Great Britian secured additional treaties focusing primarily on commerce.

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan (Harris Treaty)

The United States also signed a second treaty with Japan in 1858, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce or Harris Treaty named after the Consul-General of the United States of America for the Empire of Japan, Townsend Harris.

The articles of this treaty built on those laid out in the Kanagawa Treaty and also added new clauses:

-

Opening of the following ports (in addition to Shimoda and Hakodate) on the dates respective dates appended. Kanagawa (4th July 1859), Nagasaki (4th July 1859), Nee-e-gata – Niigata (1st January 1860), Hiogo (1st January 1863).

-

Americans may freely buy from and sell to Japanese any articles without the intervention of any Japanese officer, Munitions of war shall only be sold to the Japanese government and foreigners, No rice or wheat shall be exported from Japan as cargo, but all Americans residing in Japan and ships for their crews and passengers shall be furnished with sufficient supplies of the same, The Japanese government will sell from time to time at public auction any surplus quantity of copper that may be produced.

-

Duties shall be paid to the government of Japan, on all goods landed in the country, and on all articles of Japanese production, that are exported as cargo according to the tariff hereunto appended.

-

If Japanese custom-house officers are dissatisfied with the value placed on any goods, by the owner, they may place a value thereon, and offer to take the goods at that valuation. If the owner refuses to accept the offer, he shall pay a duty on such valuation. If the offer be accepted by the owner, the purchase money shall be paid to him without delay, and without any abatement or discount.

-

Supplies for the use of the United States navy may be landed at Kanagawa, Hakodate and Nagasaki, and stored in Warehouses, in the custody of an officer of the American government, without the payment of any duty. But if any such supplies are sold in Japan, the purchaser shall pay the proper duty to the Japanese authorities.

-

Importation of opium is prohibited, and any American vessel coming to Japan, for the purposes of trade, having more than three catties (four pounds avoirdupois) weight of opium on board, such surplus quantity shall be seized and destroyed by the Japanese authorities.

-

All goods imported into Japan, which have paid the duty fixed by this treaty, may be transported by the Japanese, into any part of the empire, without the payment of any tax, excise or transit duty.

-

No higher duties shall be paid by Americans on goods imported into Japan, than are fixed by this treaty, not shall any higher duties be paid by Americans, than are levied on the same description of goods, if imported in Japanese vessels, or the vessels of any other nation.

-

Duties shall be paid to the government of Japan, on all goods landed in the country, and on all articles of Japanese production, that are exported as cargo according to the tariff hereunto appended.

-

All foreign coin shall be current in Japan, and pass for its corresponding weight of Japanese coin of the same description, Americans and Japanese may freely use foreign coin in making payments to each other, The Japanese government will for one year after the opening of each harbour, furnish the Americans with Japanese coin, in exchange for theirs, equal weights being given and no discount taken for recoinage, Coins of all descriptions (except Japanese copper coin) may be exported from Japan, and foreign gold and silver uncoined.

-

The Japanese government may purchase or construct in the United States, ships of war, steamers, merchant ships, whaleships, cannon, munitions of war, and arms of all kinds, and any other things it may require. It shall have the right to engage the United States, scientific, naval and military men, artisans of all kind, and mariners to enter into its service. All purchases made for the government of Japan, may be exported from the United States, and all persons engaged for its service may freely depart from the United States (provided) that no articles that are contraband of war shall be exported, nor any persons engaged to act in a naval or military capacity while Japan shall be at war with any power in amity with the United States.

-

(Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan (Treaty of Amity and Commerce, Harris Treaty) - “the World and Japan” Database, n.d.)

Increase of trade between the west and Japan as a result of the unequal treaties

Recall that prior to the signing of the first unequal treaties with the west, Japan did already have some contact and trade with the outside world, which occurred in Nagasaki on Dejima Island where trade with the Dutch East India Company and China through the Ryukyu Kingdom was regulated. However, in the last years of Sakoku, trade had been falling considerably.

Dutch imports during this period included woollens, silks, velvets, cotton goods, gold, silver, tin, and mercury, but was missing sugar, which was formerly a leading item. Private importations included spices, chemicals and trinkets traded for Japanese products.

Dutch Trade (Fl refers to Florin/Guilder – Currency of Netherlands from 1434 until 2002)

However, by signing the treaties, Japan shifted from autarky to free trade, which triggered a sharp increase in trade since businesses were attracted to the good communications, well developed commercial network and national markets of many valuable commodities which encouraged them to trade. By 1873, Japan’s imports per capita were three times higher than China.

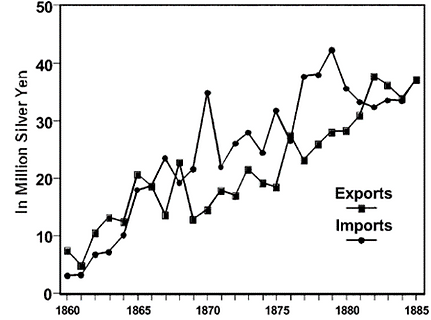

Development of Japan's external trade, 1860 - 1885

Source: Sugiyama (1988, table 2-4)

Import tariffs were also kept low at around 5%. This encouraged more trade of goods between Japan and the West which gave Japan greater access to western technology, goods and information, which was an advantage of the various unequal treaties not recognised at the time.

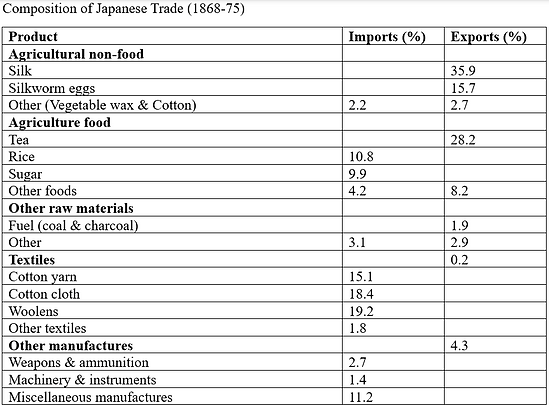

This free trade allowed the Japanese economy to specialise to its comparative advantage and ultimately reap the benefits of efficient allocation of resources. Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011)

For example, as seen in Fig. 3 (below), from 1868 – 1881 raw silk became Japan’s main exportable good, followed by tea, copper and coal. The earnings from exporting these goods financed importing capital goods such as machinery, trains and steamships which allowed Japan to industrialise.

'

Composition of Japan's exports: 1868-1881 Source: Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011) pg. 15

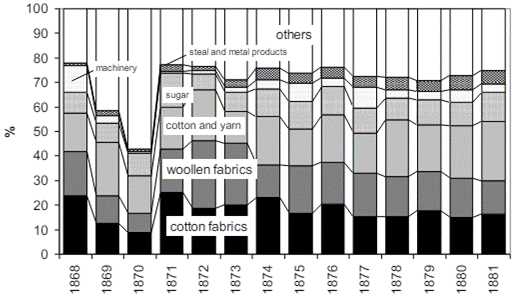

In Fig. 4 (below), it is evident that textile commodities like cotton fabrics, yarn and woollen account for more than 50% of total imports.

This is likely because the cotton industry in Japan which was the largest source of demand for these commodities was an important aspect of the country’s industrial development due to its high production and export rates which required a high and steady volume of input which was supplied through imports from the west during this time. Abe (n.d.)

Japan’s static gains from trade was estimated to be around 8 – 9% of its GDP during 1868 – 1875. Bernhofen and Brown (2004, 2005)

Composition of Japan's imports: 1868-1881 Source: Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011) pg. 15

Dissatisfaction among the Samurai clans

Unfortunately for the Tokugawa Shogunate, the benefits of opening the country up to trade was not on the minds of their vassals.

Although Japan was undergoing a period of modernisation through increased trade with the west, the treaties signed by the Shogunate were perceived to be relinquishing Japanese sovereignty, especially the treaty clauses which granted foreigners extraterritoriality (if they committed crimes on Japanese soil they were to be judged and sentenced under the laws of their home country, instead of Japanese law), and opened up ports to trade.

The Shogunate’s inability to refuse to sign such humiliating treaties, and its perceived willingness to sign many such treaties with several western countries was viewed by many samurai and daimyo to be a sign that the Shogunate was weak and unable to protect Japan. This sentiment was especially prevalent among the Tozama daimyo, the outsider lords who ruled domains far away from Edo and were seen as not trustworthy by the Tokugawa. Sasajima (2017)

In particular, the Shimazu clan of Satsuma and Mori of Choshu domains although bitter enemies, found a mutual threat in the Tokugawa Shogunate, and after a series of negotiations came together to form the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance/Satcho Alliance (薩長同盟).

This alliance was only possible through the efforts of Sakamoto Ryoma and Nakaoka Shintaro from Tosa Domain and Saigo Takamori from Satsuma in mediating both parties during their discussions. A deal was reached whereby Satsuma would supply Choshu with much-needed modern firearms procured from Scottish merchant Thomas Glover and, Choshu would reciprocate by supplying Satsuma compounds in Kyoto. Oskow (2022)

The new alliance rallied around the cause of restoring Emperor Meiji to his rightful place as ruler of Japan under the slogan of Sonno Joi, which translates to Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians.

Boshin War

Before the Boshin War began, foreign powers started to picked sides, the British supported the Imperial faction, whilst the French backed the Shogunate faction.

The conflict itself lasted one year, from 1868 – 1869 and took place over a series of battles, however before the start of the war in November 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th and last Tokugawa Shogun initially resigned from his post as Shogun in an attempt to appease the upstart Imperial faction before a war broke out so he still could hold onto some political influence and relevance in the new government, however this did nothing to forestall the inevitable conflict.

In fact, members of the Sat-cho alliance forged an Imperial Edict calling for violence against Yoshinobu, and called a meeting where the former Shogun was stripped of his domains and titles.

Upon hearing this, Yoshinobu wrote a message with a formal complaint and sent it to the Imperial court. The message was supposed to be delivered by Tokugawa forces, but they were refused entry into Kyoto by troops from Satsuma and Choshu, and attacked. This battle in 1868 became known as the battle of Fushimi-Toba, it occurred over four days near Kyoto, and was won by the Imperial faction comprising of forces from Satsuma and Choshu equipped with western firearms like Armstrong howitzers and Gatling guns despite initially being outnumbered by the Tokugawa loyalist faction three to one.

A naval battle occurring at roughly the same time in Awa Bar near Osaka between Satsuma and Tokugawa vessels was won by the Tokugawa faction.

After witnessing the outcomes of the first few battles, many daimyo who initially sided with the Tokugawa began to defect to the Imperial court.

In February 1868, Osaka Castle serving as the headquarters of the Shogunate in Western Japan was seized by forces of the Imperial faction.

In March, British Minister Harry Parkes concluded a neutrality agreement among the European countries to put a stop to western powers overtly supporting either side of the Boshin War.

Saigo Takamori himself led troops of the Imperial faction across Japan in May 1869 to surround Edo, and the shogunate’s capital city unconditionally surrendered shortly after.

In spite of the fall of Edo, the shogun's navy commander Enomoto Takeaki refused to surrender eight of his ships and instead sailed north in the hopes of joining forces with other northern domain warriors who remained faithful to the shogunal regime, including the samurai of the Aizu clan.

When Enomoto arrived in Hakodate on the southern tip of Hokkaido Island in October 1868, his forces took control of the Goryokaku fort and started to fortify their position. In December, the short lived breakaway state, the Republic of Ezo was declared. It quickly formed an alliance with various daimyo in northern Honshu Island who were opposed to the new Imperial government.

The new government launched a campaign against the Alliance in 1869 which lacked enough support and resources to effectively fight back. Finally in May 1869, the Battle of Hakodate ended with the surrender of Enomoto Takeaki and with the fall of the Goryokaku fort and the Republic of Ezo, the last impediment to Imperial rule was swept away. Writers (2017)

CHAPTER TWO

Industrialisation and Westernisation during the Meiji - Taisho Periods

The Japanese Industrial Revolution

Arguably, the period of industrialisation in Japan has its roots in the late Edo period. It was during this period in 1858 when the five commercial treaties between Japan and the aforementioned countries, the US, Netherlands, Russian Empire, Great Britain and France were signed, that the country began to experience a change in political and economic strategies to cope with the impacts of trade with the West, called kogi yoron (government by public deliberation) and fukoku kyohei (enrich the country, strengthen the military). Banno and Ohno (2010)

The end goal of fukoku kyohei was for each domain to set up their own trading firm to procure products from across Japan which were in high demand for export, and use the proceeds from exporting these goods to purchase cannons, guns and military ships from the west in order to bolster the military power of the individual domain to better compete with other domains as well as the Shogunate. Banno and Ohno (2010)

Reverberatory furnaces capable of producing iron cannons domestically were also established in the 1860s due to a growing concern for Japanese defense concerns. This was the first time Japan ever witnessed a factory-like organisational production system, which is why Professor Eric Pauer of the University of Marburg argues that the roots of the Japanese industrial revolution is during this time period. Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011)

The Meiji Government’s Development Policy

In order to prevent Western influences from dominating the industrial sector, the Meiji government began implementing the shokusan kogyo (develop industry and promote enterprise) policies in the 1870s. These policies focused on building a national banking system, investing in the telegraph, railroad, and postal networks, selling publicly owned factories, and lending and selling equipment to the private sector.

Due to these measures, there was a brief era of direct government ownership and control over business. Additionally, after the early 1880s, the bureaucracy and the zaibatsu (large family-run business conglomerates) formed a unique alliance in which the zaibatsu essentially partnered with bureaucrats, politicians and the military to set national policies. This partnership would continue from the Meiji period through the Taisho Period all the way up till the Showa Period when military controls were imposed in the 1930s. Genther, P. (2020)

Japan adopted a decentralised national banking system in 1872. This system which was similar to the American model prior to the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, allowed local economies to establish their own banks that would issue notes without the need for a central bank. During the 1870s, these "national banks" expanded quickly throughout the country. As a consequence, Inflation was brought on by the rise in the money supply that accompanied the opening of more banks issuing notes, yet an argument can be made that this increase in the local money supply greatly benefited local business and industry. Hashino and Saito (2004)

Case Study: Impact of Shokusan Kogyo on the Cotton Spinning and Silk Reeling Industries

Since the cotton spinning and silk reeling sectors were two of the best-performing in the ‘modern’ sector prior to 1920, they are good examples to highlight for an idea of how industrialisation impacted various industries in Japan during the Meiji Period.

One significant difference between the two industries to note is that Cotton spinning did not exist as its own industry during the Tokugawa era.

Cotton mills used raw cotton imported from China and India were established using Western factory systems. A detailed investigation of company records discovered that spinning companies had a strong growth orientation, aggressively sought out the most advanced technology, and gave particular attention to coordination with other spinning companies and government agencies. Being among the first industries to introduce joint stock company structures in Japan helped them raise money in the capital markets for expansion.

On the other hand, silk reeling was traditionally a rural industry. Farm women had woven raw silk for centuries, which merchants would then gather and send to weaving centres. During the Meiji period, the weaving segment of the silk industry evolved into a factory business, supplying uniform silk yarn to quickly mechanising American weaving factories. Suwa, located in Nagano Prefecture, became the principal hub of this industry. A successful collection of appropriate and effective institutions evolved in Suwa district by using econometric and game-theoretic methods. Hashino and Saito (2004)

The results of this shift in silk reeling were similar to the large-scale cotton mills' changing patterns. Although both industries adopted a factory structure, their technological features remained labour-intensive. Kiyokawa made a strong case that the high labour intensity of the cotton industry was directly related to the early adoption of ring frames by Japanese cotton mills, while Nakabayashi showed that Suwa's productivity growth was largely dependent on the interactions between the incentive schemes used by silk linters and the work effort of their female employees.

Therefore, it should be stressed that Meiji Japan's cotton spinning and silk reeling industry made the decision to use "appropriate technology." The overall pattern of Japan's industrialisation up until 1920 was significantly labour-intensive due to the weight of the traditional sector, which was overly labour-intensive according to the factor endowments of the nation. In turn, this had a significant impact on how the nation traded in the industrialising world market.

Ideological Changes

As more foreign teachings, and activities increasingly penetrated Japan, the idea of Sakoku was gradually discredited and replaced with kaikoku as the new Japanese virtue roughly corresponding to the conclusion of the Boshin War which ousted the Tokugawa Shogunate from power and replaced it with a new Imperial government led by Emperor Meiji.

Under kaikoku, fundamental institutional changes were enacted in Japan.

Firstly, the creation of an emperor-centric national polity. Recall that for centuries prior to the Meiji Period, the emperors of Japan held virtually no authority, were cloistered monarchs who spent all of their time in Kyoto and were used to legitimise the rule of a Shogunate, or relegated to obscurity and sometimes the brink of poverty during prolonged periods without centralised rule, such as the Sengoku Period. After the Meiji Restoration, however, the emperor emerged from the old capital of Kyoto with newfound powers as became an active front of authority instead of just a passive source to legitimise someone else’s rule. Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011)

Secondly, was the formation of a modern nation state merging Confucian administrative principles with western imports in an effort to learn from the West and eventually renegotiate the unequal treaties that Japan had signed.

Renegotiating the unequal treaties

By 1878, revising the unequal treaties was the top diplomacy agenda for Japan, and the foreign minister Munenori Terashima first attempted to negotiate with the United States to regain Japan’s right to set tariffs, which could be an important source of revenue for the government to offset the costs of the Seinan War.

At first the United States accepted Japan’s request to set tariffs autonomously, however the progress was undone by Britain and Germany both of whom rejected it.

In 1894, the clause of extraterritorial rights was abolished in the Japan-Britian Commerce and Navigation Treaty. This was also extended to agreements with fourteen other nations including the United States, France, Germany and Russia. This was possible because of a common concern between Japan and Britain about the Russian Empire’s southern expansion into Asia.

1911 is the year in which Japan established itself as a developed society on the international stage. In this year, the Japan-Britain Commerce and Navigation Treaty was completely revised. Japan’s victory over China in the first Sino-Japanese War (1894 – 1895) and against Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904 – 1905) were likely instrumental in the revision.

1911 also saw the signing of the new Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and the US which restored the right of the Japanese government to set their own tariffs autonomously and brought an end to the tariff restrictions set by the unequal treaties.

In 1920, the acceptance of Japan as a significant member of the international community is evident when it alongside, France, Britain and Italy became permanent members of the League of Nation’s security council (precursor of the United Nations). Atsumi and Bernhofen (2011)

Impacts of Renegotiating the Treaties

By regaining their right to autonomously set tariffs, the government was able to shield their nascent domestic industries from competition by established foreign companies, they accomplished this by imposing high tariffs on imported goods.

In addition, tariffs on certain imported goods which the government aimed to increase production of at home were increased particularly higher which gave a competitive edge to Japanese manufacturers since they could price their goods cheaper than the foreign competition and naturally sell more of them to consumers. Examples of such goods would include textiles, machinery and consumer goods.

In renegotiating the unequal treaties, Japan also secured more favourable terms in regards to international trade and the improved legal and economic landscape in the country attracted valuable foreign investment and facilitated a greater technology transfer which accelerated the pace of industrialisation.

Origins of the Zaibatsu

As the Industrial Revolution was ramping up in Japan, the county was overcome by a desire to catch up to the more developed nations in the west. Fortunately for them, because Japan was a relative latecomer to the modern capitalist world, they did not need to invest time and money to invent and develop advanced technology or institutional structures, but only to introduce what had already been created by the west into their own country.

The urge to catch up to advanced nations and become an equal to the west, coupled with the ability to learn from and adopt new technologies that had already been invented without the need to devote resources to create them from scratch created a core competency in Japan’s economy which focused on accumulating organisational capacity to facilitate their modernisation. Yonekura, S., & Shimizu, H. (2016)

After all, the problem Japan faced was one of insufficient key resources necessary for industrialisation which was the key to modernisation. Japan in the early Meiji Period lagged behind the west in terms of infrastructure, capital, human resources, as well as scientific and technical knowledge due to the 200 year period of Sakoku.

The breakthrough to solve the crucial hurdle of resource shortage came in the form of large business conglomerates known as ‘Zaibatsu’ meaning “financial cliques”. These groups were an organisational innovation which consisted of several diversified businesses owned by a single or extended large family. They allowed Japan’s economy to concentrate managerial resources in a few large companies and enabled them to be put to multiple uses.

Table of prominent Zaibatsu during the Meiji Period

Organisation Structure of a Zaibatsu

The Zaibatsu are often referred to as "family konzerns”. A konzern is a type of business group found in Germany, essentially a group of companies which have been merged into one single entity with a unified management, consisting of a controlling company and various companies under their control. In the case of the zaibatsu, each were controlled by a single family, most of the owned capital of the businesses under the Zaibatsu's control was provided to the holding companies in the form of monopolistic funding distributed by the family members operating the Zaibatsu.

A Zaibatsu is structured with a holding company at the top which is operated by the family and below it, various companies operating in different industries ranging from manufacturing, to commodity circulation and banking.

A very high degree of capital accumulation was achieved through self-financing. Consequently, the various financial organs under the control of the Zaibatsu also existed as institutions, but their role was to expand Zaibatsu control rather than to finance Zaibatsu controlled businesses. Kazuo (n.d.)

Rise of the Zaibatsu

The success of the Zaibatsu early in the Meiji Period lay in how they built upon early organisational innovations in the process of evolving into modern businesses. For instance, while the Japanese government was still in the beginning of its modernisation initiative, they first established state-owned enterprises in an attempt to set industrialisation in motion.

This move had mixed results but damaging costs since it placed a massive burden on the coffers of the state which did not help the rising inflation problem the government was trying to deal with during this time.

These factors contributed to the fateful decision to pivot from direct state action, to an indirect intervention policy, and the government started to promote private sector involvement in formerly public businesses including the banking, shipping, cotton spinning and mining industries.

This opportunity was available for both established firms which had been operating since the Edo period and survived the upheavals of the Meiji Restoration, and more newly launched firms which were started after the restoration. Of course, in both of these groups, only firms with the capability to raise and accumulate the necessary organisational capabilities like a flexible and talented workforce were able to respond and take advantage of this. Yonekura, S., & Shimizu, H. (2016)

Case Study: Mitsui

The Mitsui zaibatsu is one of the oldest and largest zaibatsus in Japan.

Their origins date back to 1673 during the Edo period, when Mitsui Takatoshi, the fourth son of the Mitsui merchant family opened Echigoya, a drapery shop which sold kimonos in Edo (Tokyo).

Takatoshi’s target market was the middle class of the city, and he pioneered an innovative merchandising style by rejecting the ambiguous pricing practice of the contemporary kimono shops, attaching fixed prices to his kimonos which were non-negotiable, non-discountable and most importantly, affordable.

This new business style drew popularity among Takatoshi’s targets of middle class customers, and also enabled him to cultivate a close relationship with the Tokugawa shogunate. The money he earned from this business allowed him to start a second business in 1683, which dealt in money exchange. Both his businesses would be appointed as official purveyors to the shogunate.

Over time, Takatoshi’s businesses grew with the prosperity of Edo which allowed him to open a shop in Osaka which was the second largest city in Japan. Takatoshi himself would pass away in 1694.

Later in 1710. The sons of Takatoshi would pool their inheritance into a collective fund to start the Mitsui Omotokata, a holding company to regulate and oversee the affairs of the extended Mitsui family. This holding company initially consisted of just nine families and controlled the finances and management of the drapers’ shops and money exchange houses, and the Mitsui family received biannual cash dividends at a fixed percentage of the proceeds from the businesses. Yonekura, S., & Shimizu, H. (2016)

Social Upheaval

In the mid-nineteenth century, a series of crises ranging from a famine caused by serious crop failures, an earthquake in 1855 in Edo, samurai and farmers defaulting on debts and economic stagnation led to the draper business of Mitsui to begin falling behind in its payments, while the money exchange service with the shogunate and daimyos becoming a burden on the family’s financial resources.

After Japan’s conclusion of treaties with the United States and other western nations which opened up many trade ports for international trade, the Tokugawa shogunate was plunged into a financial crisis of rapid inflation caused by the outflow of gold. The position of the shogunate itself was also increasingly at risk as their willingness to sign the unequal treaties and agree to humiliating terms were perceived as weak by many clans, this provided an opportunity to the Sat-Cho alliance as they began the Boshin war to restore the Emperor to power and depose the Shogunate.

To try to seek funds to pay for the war effort and protect their position, the shogunate desperately approached large merchants like the Mitsui for financial support, however, since the family had already committed a significant amount of money to the Shogunate, they were forced to seek outside assistance from Minomura Rizaemon, the son-in-law of a vegetable oil and sugar merchant.

Minomura successfully renegotiated the shogunate’s financial demands on the family by one-third and was rewarded with an appointment as the chief executive of the Mitsui family’s money changing business in 1866.

Turning point

In his new position, Minomura predicted the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and advised the Mitsui family to renounce them and instead pledge financial support for the new government.

In 1867, his warnings came to pass as Tokugawa Yoshinobu returned his political power to the Emperor and the new Meiji government was established the very next year.

Despite the new government’s limited fiscal resources and political power, it aimed to rapidly industrialise and create a strong military. Minomura spotted an opportunity and established strong ties with them through Inoue Kaoru, and secured important positions in finance, trade and exchange. For the Mitsui family however, the close ties to the government was initially a financial bane as they were asked to provide 300,000 ryo to help secure the government’s fiscal foundation and widen its revenue base.

Even for a wealthy family like the Mitsui, this was a large sum, but Minomura’s decision to liquidate some family properties to accumulate the necessary funds won the family the government’s trust which opened up stronger political connections for Mitsui.

Business Opportunities

The Meiji government was aware that they needed to lay the foundations for a modern capitalist economy by establishing a stable monetary and banking system to solve the stagnation of consumer production and high import costs. To balance Japan’s trade, entire industries would need to become capable of competing with foreign counterparts.

Minomura saw the importance of restructuring Mitsui’s traditional businesses and started by hiring new staff members from outside the family with the necessary knowledge and skills to develop new businesses. Among the new hires were Takashi Masuda (founder of Mitsui Bussan – domestic trading arm of the Mitsui business), and Nakamigawa Hikojiro (reformer of the Japanese banking business).

These changes were not viewed favourably by traditionalist members of the Mitsui family however, as they were perceived to be too risky. These members preferred to simply hold real estate which was considered to be a safe asset as opposed to developing and exploring new, untested fields of business.

The entrepreneurs of the family needed money to fund their new business ventures, money which was not going to be provided by the traditional merchants easily. To solve this, Minomura came up with a plan to establish a limited-liabilility holding company which could allow the capital of the traditional merchants to be used to pay for the new ventures.

Setting up of New Enterprises

In the early 1870s, Minomura planned to establish a bank and send seven staff to the United States to learn modern banking techniques. To follow a banking regulation established by the Meiji government in 1872, Japan’s first national bank, the Dai-ichi Kokuritu Ginko (Daiichi National Bank) was founded, capitalised through public subscriptions and contributions from both the house of Mitsui and Ono Gumi (another exchange house founded in the Edo period).

Minomura believed that it would be best to concentrate the financial resources of Mitsui in banking with an independent Mitsui bank. To that end, it would be necessary to cut off the old kimono business (draper’s shops) from the family’s portfolio.

As Mitsui Omotokata was the organisation controlling the family’s business matters, it had an unlimited liability in the draper’s shop business, which meant the entire Mitsui family’s finances was at risk if the kimono shop business failed. There were no laws which granted limited liability to stockholders during the 1870s. Hence, in order to protect the new bank Minomura was planning to establish, the kimono business needed to be separated.

A proposal submitted by Minomura to Okuma Shigenobu (finance minister) was approved on the one condition, that the stockholders of the bank would bear unlimited liability. With this condition being accepted, the first private bank in Japan, Mitsui Bank was established in 1876.

Despite Minomura’s acceptance of unlimited liability in the bank, he still intended to minimise any possible risk to the Mitsui family from the Mitsukoshi business while still maintaining managerial control in order to enhance the individual potential fields of the new businesses. Thus to achieve both goals at the same time, several Mitsui personnel were appointed to the board.

No regulations governing limited liability had yet been recognised under Japanese laws, so the organisational set-up also had the unintentional benefit of furthering the separation of ownership (capital) and management which gave the entrepreneurs a freer hand to develop new businesses.

Minomura had also included in his plans for a private bank, the proposal to form a trading company. International trade was still new to Japan so expertise was quite limited. It was also still largely dominated by the west. Masuda Takashi was singled out to manage this new enterprise. He had previously served as an interpreter and worked for the new Ministry of Finance immediately after the Meiji Restoration. Later, he joined Senshu-sha, a trading company started by Inoue Kaori in 1874 before being hired to establish the trading company for Mitsui.

It was believed that rapid industrialisation for Japan was possible if the country imported advanced technology and promoted exportation to acquire foreign currency. Minomura spotted the money that could be made with international trade, so he offered Masuda the opportunity to lead the Mitsui family’s new trading enterprise, Mitsui Bussan in 1876.

Of course, the traditionalist members of the Mitsui family also were not interested in international trading as it was completely alien to them. The primary reason for their disinterest was the risk associated with international trade. So once again, Minomura would need to devise an organisational structure which would not impose the obligation of unlimited liability on the Mitsui family.

The newly established Mitsui Bussan was a unlimited partnership between the seventh son of Takafuku (head of the family), and the third son of Takayoshi (brother of the family head) with sixteen employees, but otherwise, had no ties with either Mitsui Omotokata or Mitsui Bank. The initial investment was received in the form of a loan courtesy of Mitsui Bank, Mitsui Omotoka on the other hand, was not willing to commit resources to Mitsui Bussan.

Masuda established a head office located in Tokyo as well as three branch offices located in Yokohama, Osaka and Nagasaki. He also promoted college graduates from top universities in Japan such as the Tokyo Higher Commerce School (Hitotsubashi University) and Keio University. Being able to secure such advanced knowledge and talented workers skilled in accountancy and English speaking was a huge advantage and would be instrumental to the development of Mitsui Bussan’s growing business in international trade.

Minomura passed away in 1877, however the restructuring initiatives were continued by Masuda. In 1885, the Meiji government asked all private chartered banks to return the right to print their own money as well as their paid-in capital to the newly created Bank of Japan (central bank of Japan). This was a blow to the bank partly because their financial standing had been deteriorating due to their overextension by opening several branches in less-economically important and viable locations in keeping with its designated public duties.

Appointment of new managers for the business ventures

Mitsui Bank’s financial woes continued until 1891 when Masuda and the Mitsui family appointed Nakamigawa Hikojiro, a young businessman to reform the bank.

Nakamigawa spent three years studying western political, economic and business systems in London and became president of Sanyo Railways (railroad company established in 1887) with the backing of Inoue Kaoru.

When he was hired by Mitsui Bank, his first order of business was to employ undergraduates of Keio University which was his alma mater, delegated important managerial decisions to his new team of managers, and introduced a performance-based compensation system. He also repositioned Mitsui Bank from a public agency to private banking, believing that the various connections inside the government prevented the bank from modernising its business, and began to clean up Mitsui’s public agency businesses with the goal of improving Mitsui Bank’s finances and modernise the business.

In 1881, the new minister of finance Matsukata Masayoshi introduced a policy of financial austerity with rigid budget constraints, withdrawl of unconvertible money and increased privatisation of public businesses wherein public works and mines were sold off to private buyers, largely zaibatsu.

Nakamigawa and Masuda both aimed to transform the Mitsui family’s businesses into modern conglomerates. To that end, they would take advantage of Matsukata’s privitisation policy to acquire new assets to generate revenue. A prominent example would be the state-owned Miike coal mines which had been government run from 1873, but by 1888, the government was requesting for bids from private buyers to purchase the mines.

Masuda spotted an opportunity as he envisioned the energy industry playing a central role in Japan’s industrialisation and considering that Mitsui Bussan already had a relationship with the mines through their exclusive contract with Miike coal signed in 1879. He was also aware of the extent of the coal deposits in the mines because of his government appointment as agent for coal exports, and knew that acquiring the mines would be a massive boon for both Mitsui Bussan and the Mitsui zaibatsu.

Masuda made a bid of 4,555,000 yen which was an unprecedented amount of money at the time, this led to skeptics labelling him “insane” for offering such a high bid.

Developing the Miike mines

At the time of Mitsui’s purchase of the Miike mines, the same traditional mining practices that had been used for centuries still remained widespread, such as the use of abundant and cheap manual labour in the form of convicts from prisons, and social outcasts.

Masuda recognised that introducing advanced mining techniques from the west would be able to increase the productivity of the mines, and an important role would be played by the chief engineer at Miike, Dan Takuma in the modernisation and development of the mines.

Dan returned to Japan in 1878 after completing his studies in mining engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 1884, he transferred to the Ministry of Engineering and started working for Miike Mines after serving as an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo and Osaka Engineering School.

Restructuring of the Mitsui Zaibatsu

In contrast to the multidivisional organizations emerging in the US, Mitsui created a conglomerate in the form of a holding company.

From the perspective of transaction cost theory, this structure looks expensive because it required each individual subsidiary to have redundant indirect tasks (e.g., people, general affairs, financing, corporate strategy planning)

(see Williamson 1975 and Chandler 1962)

Rationale: The multidivisional structure (M-form) eliminates redundant costs by centralizing each division's indirect functions and enabling the allocation of administrative resources for the entire organization.

Three factors led Mitsui to select the holding company structure.

The first was the disagreement between the new business entrepreneurs and the traditionalist family members. Although the Mitsui family had a 200-year history of being risk averse, the family needed to hire skilled outside entrepreneurs to help them weather the Meiji Restoration and the ensuing social and economic turmoil. Conversely, the company owners considered the Restoration to be a fantastic chance to start new ventures.

The second was the lack of understanding of contemporary business and technology was the second factor in Mitsui's decision, leaving the older merchants no option except to allow their managers to take on new ventures. Therefore, the entrepreneurs' separation from the holding firm was preferable.

Lastly, there were a plethora of commercial opportunities in the early Meiji period, from railroads to banks, among others, trade, mining, shipping, shipbuilding, and textiles. However, as the auction for the Miike mines demonstrated, there was intense competition between established and emerging business groupings. Since time was of the essence, the zaibatsu found it simpler to create subsidiaries under the holding company structure than to internalize through divisions.